Media Platform &

Creative Studio

Magazine - Features

In conversation: Kirsty O’Brien

Joana Alarcão

In this interview, we spoke with Kirsty O'Brien, a contemporary artist from Redcar, Cleveland, whose powerful practice explores the intersection of industrial heritage and environmental consciousness. Working from her hometown in the shadow of former steel works, O'Brien creates experimental paintings that reflect the complex relationship between heavy industry and landscape transformation. Her innovative approach involves combining household paints, varnishes, and unconventional materials to mirror the chemical processes of steelmaking while addressing urgent environmental concerns.

14 August 2025

.jpg)

Kirsty delves deep into the relationship between the industrial landscape of the Tees Valley and the natural landscape surrounding her hometown of Redcar, capturing the detritus from industrial sites that wash up on the shoreline, and the looming grey towers on the horizon through abstracted paintings. She applies textures to surfaces, using found paint and added aggregates combined with multiple layers of paint with a process that encourages the material to make some creative decisions. There is an inviting depth to her work, as if the abstract compositions are a microcosm of another world. Her painting language combines a free approach to mark making with structured geometric lines, further documenting the industrial/natural divide.

Written by Aphra O'Connor, Sculptor and Curator of Artist Programmes, Redcar Palace.

Could you please start by giving us an overview of your practice and the steps you took to become the artist you are today?

I spent my childhood drawing in my bedroom in Redcar, Cleveland, UK, usually of animals from books and landscapes I had seen. I followed the usual art curriculum, but I always came back to the landscape. Having explored it using different materials and trying realistic and abstracted interpretations, momentum with my practice took off from my third year at Northumbria University, Newcastle, UK where I created a series of experimental works about the first closure of the Blast Furnace, part of the steel works, at South Gare near Redcar. I used old products such as household paint, varnish and outdoor paint not only to save money, but to use the unused and to experiment with each type of paint to see what it did on the surface of the canvas. The outcome of this was a successful series of paintings reflective of steel processes, the surrounding landscape and experimental use of paint.

Following my graduation, financial constraints brought me back home and I have dipped in and out of my practice since 2010. Focussing on having a job impacted how I engaged with my practice, and I felt I had little opportunity to have a successful art career. I continued in part, because I love to create. My practice remained largely the same, focussing on the second and final closure of the Blast Furnace in 2015 and the impacts of heavy industry on the landscape. After the birth of my son, I decided to reengage with my practice. I submitted a painting from 2019 to an open call at Redcar Contemporary Art Gallery for the 2024 Summer Show titled ‘Environment’, and I was successful. Inspired by the exhibition theme, I started to think more about the impacts of heavy industry on the land, which has led to a new series of paintings exploring my thoughts and feelings around the human impacts on our natural environment and ecosystems. I have gone on to have a successful solo show at Redcar Palace, Tees Valley Arts in Redcar and I feel I have hit my stride..

In your statement, you mention that your pieces combine different products on surfaces to reflect processes within the industry and how these processes have changed the shape and composition of the landscape. Could you elaborate on these conceptual and technical aspects?

During my degree show and in the years following, I spent some time looking at steel making processes, such as the chemical reactions, how steel was poured and sculpted, how waste was created and then disposed of, or released, and how combining raw materials created steel. Those concepts informed how I handled the paint, how I poured it, how I purposely combined water-based and oil-based paint so they would work against each other and often I would be surprised at how these opposing products would work well with each other and create effects on the surface which were unexpected.

As the years have gone on, I have learned about how these differing products work with each other and used those techniques to create a specific outcome. I was asked to create a piece of work for a group exhibition about the Black Path, a local path which runs alongside a train track, coke ovens and other heavy industry. I had a clear idea that I wanted to create a piece of work which looked like an open coke oven door, and through my years of experimenting, I knew how I would use acrylic paint and black gloss to create the effect I wanted. Though I have spent a long time experimenting with paint and other products, I have still found new ways of using paint, and this has led to successful paintings around the shape and composition of our landscape.

I am currently focussing on carefully applied layers, to reflect how our land is made up of layers which run deep and how we do not know what the impacts of historic and present contamination are having on those layers in terms of its chemical composition and ability to function as a site for human and natural life.

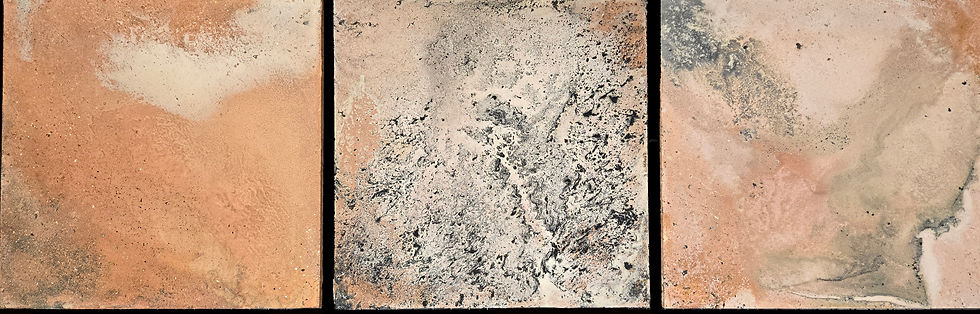

Your "Sand Triptych" responds to the River Tees dredging and the marine deaths that followed. How do you translate this complex reality into visual forms, and what materials and techniques do you employ?

The dredging of the River Tees occurred during August 2021, before I had reengaged with my art practice and it was something which had bothered me and many others due to the crustacean and cetacean deaths which followed and was dismissed by politicians and the Environment Agency, even in the face of being challenged by independent scientists. The River Tees was once so polluted, it turned black in areas and the previously abundant salmon population was decimated. Though it has been cleaned and those efforts have seen the return of salmon and a stable ecosystem, I felt that we have not learnt from the past where we polluted our waterways and land with little thought.

It was this event that got me thinking more broadly about our beaches and to dig deeper into sea coal, which still comes in with the tide. Collieries on the North East coast used to dump raw coal straight into the North Sea, and subsequently this raw material was washed up with our tides for many years. I thought about how it is normal to still see things like sea coal on the assumption that it is a naturally occurring grain which is washed up with the tide. It got me thinking about tides and those daily changing layers of natural grain and industrial waste, and I decided to make a triptych. I didn’t use sand, because I didn’t want the painting to be literal. I used salt to make the grain effect, paint to create the colour and waste water. I created one layer, moving the wet layer like a tide, and then I would go back the next day or a few days later and add the next layer.

It was a long process learning how each layer interacted, and waiting patiently to see how each layer dried before deciding to add another or decide if it was finished. By using harmful products like paint, I wanted to ensure the triptych looked as close to sand as possible to bring forward the conversation about what we are really walking on when we visit our beaches.

I feel strongly about using household paint as I noticed the conversations between the material and landscape when I glimpsed the ICI label on the back of the paint I was using at University. ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) was established in 1949 at Wilton, Cleveland, near Redcar and continues to be a prominent part of the landscape. Having worked in a decorating shop, I knew ICI used to make paint, but I had never made that connection until University. That link is important to me, because I was pouring a product made in the area directly onto the surface.

How does your family history, particularly your grandmother's stories about collecting sea coal, inform your current artistic practice?

My grandparents, particularly my Nana and Grandad, had a huge impact on my upbringing and who I am today. We are a working class family, and therefore we spent a lot of time with them during the school holidays. My Grandad used to work at the Blast Furnace, and as they would take us down to the beach at South Gare for a day out he would always pull up next to the Blast Furnace where it was closest to the fence and show us the torpedo car being filled with molten iron, which is pulled by a locomotive and destined for the BOS (Basic Oxygen Steelmaking) Plant to convert it to steel. I wrote a piece on my website, which can be found here.

It was these experiences which have directly led to where I am today. It was my grandad’s paint from his shed that I used for my degree, and I continue to use found paint in my practice today. When I was developing the idea for the Sand Triptych, I had a surprising conversation with my Gran, and she told me about how she and her cousins were made to go down to the beach and collect sea coal so they could burn it at home. She described how the dumped coal provided essential heat when they were growing up, and my nana also had the same experience as a child. It gave me much further context around the life cycle of the raw coal dumping, the detrimental effects on ecosystems and how it gave poor families essential heating. These themes are currently informing my practice, and I will be continuing to conceptually explore human interactions with the landscape.

In a written statement, Aphra O’Connor, Sculptor and Curator of Artist’s Programmes at Tees Valley Arts, Redcar, mentioned that you let materials "make creative decisions." Is this technical choice intentional, and what conceptual weight does it hold within your practice?

During my degree, I wanted the paint to make creative decisions so I could see what happened. By giving the paint autonomy to mix, collide and merge, I allowed it to make those final placements. The paint always made the final decision, because it wasn’t until the paint stopped moving and started to dry that I could see what the outcome was. It is a partnership between me and the material. I make the decision regarding sourcing the material, mixing it and applying it but ultimately the paint and material decide, often in my absence, to create the final image or the new layer.

As I have been using these experimental methods for a long time, I have come to realise how much I rely on the paint and material to help me make painting decisions. It also makes it easier to accept a finished painting if it hasn’t achieved what I was looking for. I blame the material if the outcome wasn’t what I wanted, and that helps me move on, or helps me think about what I could have done, such as not applying that colour or that layer. It is important that the paint is given autonomy, because when I think about industrial dumping or pollution, I think about how we leave it to nature to deal with that. Where did the deeply embedded pollution at the bottom of the River Tees go when it was dredged up and dumped in the sea? I envisage these particles swirling around in the murky water, trying to find a new place, and it reminds me of paint and materials mixing and colliding on the canvas, trying to find their place.

Recently, I noted a surprising conversation between a new experimental painting and a nearby Iron Museum in Skinningrove. I had never visited this museum, and we decided to take our son on a whim. During the visit, we went down the one remaining mine shaft, and I noticed salt crystals on the red brick lining the mine. There was a gentleman there who used to work in mines in India, and he explained how they had formed due to the trapped wet air from the sea, causing sea salt to crystallise. I had unintentionally created salt crystallisation on my piece ‘That Which Remains’, which is currently on show at Redcar Contemporary Art Gallery and it helped me understand how the slow drying times over winter caused the resulting salt crystallisation. This realisation will be taken forward for future paintings should I create something where salt crystallisation is important contextually.

In what ways do you reconcile the aesthetic qualities of your work with the severe implications of industrial contamination?

I don’t consider any of my work ‘pretty’, it is not commercial and is not made with the intention of it being sellable. My work is for sale when it is available in galleries, and it successfully presents steel making processes and contamination. I do seek a certain aesthetic, such as the sand and coke oven triptych, where the painting is representational. But most of the time, I create with a broad idea rather than something specific. I’m not making work with a focus on aesthetics as the context of industry, how it functions, and its relationship with nature and the land are more important. There are also aspects of steel making that I find beautiful, such as hot molten steel, the contrasting lights on the blast furnace running through the night and how industrial structures sit against a vast sunset. Industrial contamination is not a pleasant subject, yet sea coal, which exists largely due to us dumping it in the sea, sits beautifully on the beach as the tide creates beautiful black lines and shapes. If I imagine oil on top of a moving body of water, it glistens with a multitude of colours because the natural body of water is moving it in such a pleasing way. Contamination can present itself in pleasing ways, and it is important that both negative and positive aspects are captured when I’m creating in order to highlight the importance of not getting caught up in what is a good aesthetic quality.

You are planning to create works on iron oxide pollution. What new materials or techniques are you considering?

I have been holding onto this idea for a while and the reason I haven’t gone ahead with it yet is because of size constraints and I don’t want to use too many new or toxic products which I know would work well or wouldn’t work well. I had been considering resin to create a clear barrier between each layer which would be reflective of what we don’t see happening in our waterways, but it isn’t a material I have used before. I have experimented using clear PVA, but it wasn’t as successful as I had hoped. I am still thinking about how I will create the work and during this time I will be making smaller works and hoping the creative process will bring about a solution.

How do you navigate the tension between environmental advocacy and participating in the art market's consumption patterns?

If my work is bought, I want it to be bought by someone who understands the context, enjoys the aesthetic and intends to keep it as part of a personal collection. I was speaking to another artist at the weekend at the opening for the Summer Show, and he spoke to me about how our previous and current governments have made it difficult to protest and that the only outlet we seem to have as artists is to create. I can’t control the art market, and as an individual, I feel the only way I can express my point of view is to create. I am passionate about our environment, and I am very familiar with my local landscape, what shapes it, and I have seen how it has changed in a short period of time. Redcar is a small ecosystem, but I feel the issues facing it are reflective of many around the world. If my work doesn’t capture the attention of collectors, it won’t change what and how I create because I create to quieten my mind and to visualise the ideas I generate, so I am not mentally holding onto them.

Art and artists play various roles in the fabric of contemporary society. How do you see artistic practices advancing sustainability and social consciousness?

Tees Valley Arts have been supportive of my practice and allowed me to progress as an artist through a solo show, and being able to have valuable conversations with them. Galleries and organisations like this provide a platform for artists and creatives to connect with social consciousness. Last year, the Summer Show at Redcar Contemporary Art Gallery, Redcar themed ‘Environment’ covered many aspects of climate change and pollution and what I noticed with this year’s theme of “Time’ is that we have up and coming artists who are passionate about using recycled/found plastics in their work, using litter to make pin hole cameras and showcasing geological changes through time. I feel the climate crisis is already at the forefront of artists' consciousness and in turn, it is giving viewers the opportunity to consider individual views, rather than collective views. Artists are an important link to those who view and experience art as they are making more visceral connections.

What message or call to action would you like to share with our readers?

We may feel like we don’t have the power to protest or have our say, but I think there are still opportunities through creation, such as contemporary art, craft, writing, music and many other creative industries. The climate in the UK has changed drastically in the past 10 years, we are currently experiencing a drought, longer and hotter days and the environment agency has found at 110 out of 117 rivers exceed the safety limit for PFAS; if we can’t protest then creating is an important tool we can all utilise or take part in by attending exhibitions and events which advocate for the environment.

Learn more about the artist here.

Cover image:

Industrial Sands by Kirsty O’Brien.

All images courtesy of Kirsty O’Brien.

_Lauren%20Saunders.jpg)